| The

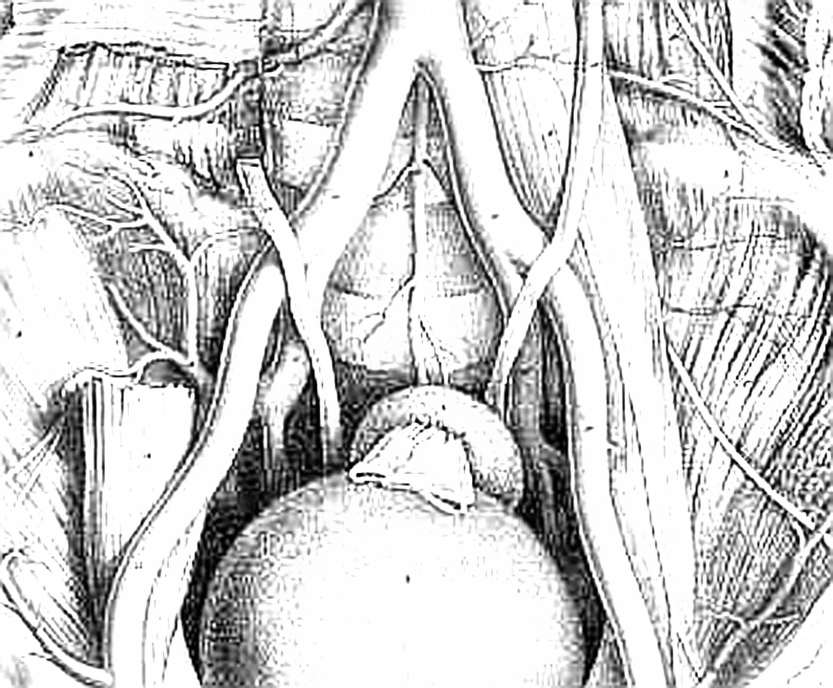

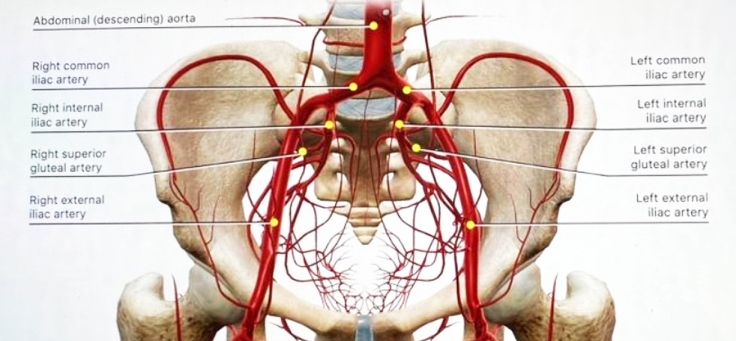

abdominal aorta bifurcates at the L4 level. The small median or middle

sacral artery arises from the posterior surface of the abdominal aorta

close to the bifurcation and descends vertically along the pelvic

surface of the sacrum. It gives rise to several small parietal branches

that anastomose with the lateral sacral arteries and to small visceral

branches that anastomose with the superior and middle rectal arteries. The aorta divides into the common iliac arteries, which travel laterally and inferiorly. At approximately the L5–S1 disc space, the common iliac arteries divide into the external and internal iliac arteries. The ureter crosses the external iliac artery anteriorly. The internal iliac artery is separated from the sacroiliac joint by the internal iliac vein and the lumbosacral trunk. The iliolumbar artery can arise from the common iliac artery, although it more commonly is the first branch of the internal iliac artery. This vessel runs superomedially, passing anterior to the sacroiliac joint and posterior to the psoas muscle. It later turns laterally and upward to divide in the region of the iliac fossa. The lateral sacral artery is usually the second branch of the internal iliac artery, although it can originate from the superior gluteal artery. These vessels, usually a superior one and an inferior one, sometimes arise from a common trunk. They pass medially and descend downward anterior to the sacral ventral rami, giving branches that enter the ventral sacral foramina to supply the spinal meninges and the roots of the sacral nerves. Some branches pass from the sacral canal through the dorsal foramina to supply the muscles and skin overlying the sacrum. Most tumors arising from the sacrum or presacral space, as well as some intraspinal masses, derive at least a part of their blood supply from the medial and lateral sacral arteries. Enlargement, displacement, or encasement of these vessels may be seen on angiography. |

|

Any comment about this page?

Your feedback is appreciated. Please click

here.

To join Scientific Spine mailing list, click here.